Extincted Aurochs

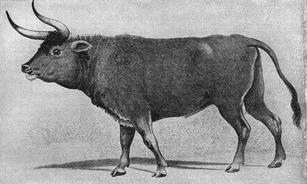

An Aurochs, from a 19th century copy of a painting owned by a merchant in Augsburg. The original probably dates to the 16th century.

The aurochs or urus (Bos primigenius), the ancestor of domestic cattle, was a type of huge wild cattle which inhabited Europe, Asia and North Africa, but is now extinct; it survived in Europe until 1627.

The aurochs was far larger than most modern domestic cattle with a shoulder height of 2 metres (6.6 ft) and weighing 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb). The aurochs was regarded as a challenging quarry animal, contributing to its extinction. The last recorded aurochs, a female, died in 1627 in the Jaktorów Forest, Poland, and her skull is now the property of Livrustkammaren in Stockholm.

Aurochs appear in prehistoric cave paintings, in Julius Caesar's The Gallic War, and as the national symbol of many European countries, states and cities such as Alba-Iulia, Kaunas, Romania, Moldavia, Mecklenburg, and Uri. The Swiss canton Uri was actually named after this animal species.

Domestication of bovines occurred in several parts of the world but at roughly the same time, about 8,000 years ago, possibly all derived from the aurochs. In 1920, the Heck brothers, who were German biologists, attempted to recreate aurochs. The resulting cattle are known as Heck cattle or Reconstructed Aurochs, and number in the thousands in Europe today. However, they are genetically and physiologically distinct from aurochs. The Heck brothers' aurochs also have a pale yellow dorsal stripe, instead of white.

The aurochs was far larger than most modern domestic cattle with a shoulder height of 2 metres (6.6 ft) and weighing 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb). The aurochs was regarded as a challenging quarry animal, contributing to its extinction. The last recorded aurochs, a female, died in 1627 in the Jaktorów Forest, Poland, and her skull is now the property of Livrustkammaren in Stockholm.

Aurochs appear in prehistoric cave paintings, in Julius Caesar's The Gallic War, and as the national symbol of many European countries, states and cities such as Alba-Iulia, Kaunas, Romania, Moldavia, Mecklenburg, and Uri. The Swiss canton Uri was actually named after this animal species.

Domestication of bovines occurred in several parts of the world but at roughly the same time, about 8,000 years ago, possibly all derived from the aurochs. In 1920, the Heck brothers, who were German biologists, attempted to recreate aurochs. The resulting cattle are known as Heck cattle or Reconstructed Aurochs, and number in the thousands in Europe today. However, they are genetically and physiologically distinct from aurochs. The Heck brothers' aurochs also have a pale yellow dorsal stripe, instead of white.

Origin:-

According to the Paleontologisk Museum, University of Oslo, aurochs evolved in India some two million years ago, migrated into the Middle East and further into Asia, and reached Europe about 250,000 years ago. They were once considered a distinct species from modern European cattle (Bos taurus), but more recent taxonomy has rejected this distinction.[citation needed] The South Asian domestic cattle, or zebu, descended from a different group of aurochs at the edge of the Thar Desert; this would explain the zebu's resistance to drought. Domestic yak, gayal and Javan cattle do not descend from aurochs. Modern cattle have become much smaller than their wild forebears. Aurochs were about 1.75 metres (5 ft 9 in) tall, while a very large domesticated cow is about 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) and most domestic cattle are much smaller than this. Aurochs also had several features rarely seen in modern cattle, such as lyre-shaped horns set at a forward angle, a pale stripe down the spine, and sexual dimorphism of coat color. Males were black with a pale eel stripe or finching down the spine, while females and calves were reddish (these colours are still found in a few domesticated cattle breeds, such as Jersey cattle). Aurochs were also known to have very aggressive temperaments and killing one was seen as a great act of courage in ancient cultures

According to the Paleontologisk Museum, University of Oslo, aurochs evolved in India some two million years ago, migrated into the Middle East and further into Asia, and reached Europe about 250,000 years ago. They were once considered a distinct species from modern European cattle (Bos taurus), but more recent taxonomy has rejected this distinction.[citation needed] The South Asian domestic cattle, or zebu, descended from a different group of aurochs at the edge of the Thar Desert; this would explain the zebu's resistance to drought. Domestic yak, gayal and Javan cattle do not descend from aurochs. Modern cattle have become much smaller than their wild forebears. Aurochs were about 1.75 metres (5 ft 9 in) tall, while a very large domesticated cow is about 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) and most domestic cattle are much smaller than this. Aurochs also had several features rarely seen in modern cattle, such as lyre-shaped horns set at a forward angle, a pale stripe down the spine, and sexual dimorphism of coat color. Males were black with a pale eel stripe or finching down the spine, while females and calves were reddish (these colours are still found in a few domesticated cattle breeds, such as Jersey cattle). Aurochs were also known to have very aggressive temperaments and killing one was seen as a great act of courage in ancient cultures

This specimen is from around 7500 BC and is one of two very well preserved aurochs skeletons found in Denmark. The Vig-aurochs can be seen at The National Museum of Denmark. The circles indicate where the animal was wounded by arrows

Domestication and extinction:-

The now-extinct aurochs Bos primigenius, which ranged throughout much of Eurasia and Northern Africa during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene, is widely accepted as the wild ancestor of modern cattle. Archaeological evidence shows that domestication of this formidable animal occurred independently in the Near East and the Indian subcontinent between 10,000–8,000 years ago, giving rise to the two major domestic taxa observed today — humpless Bos taurus (taurine) and humped Bos indicus (zebu), respectively. This is confirmed by genetic analyses of matrilineal mitochondrial DNA sequences, which reveal a marked differentiation between modern Bos taurus and Bos indicus haplotypes, demonstrating their derivation from two geographically- and genetically-divergent wild populations.

Domestication of the aurochs began in the southern Caucasus and northern Mesopotamia from about the 6th millennium BC, while genetic evidence suggests that aurochs were independently domesticated in India and possibly in northern Africa. Domesticated cattle and aurochs are so different in size that they have been regarded as separate species; however, large ancient cattle and aurochs "are difficult to classify because morphological traits have overlapping distributions in cattle and aurochs and diagnostic features are identified only in horn and some cranial element

In the 1920s two German zoo directors (in Berlin and Munich), the brothers Heinz and Lutz Heck, began a selective breeding program in the attempt to breed the aurochs back into existence (see breeding back) from the domestic cattle that were their descendants. Their plan was based on the concept that a species is not extinct as long as all its genes are still present in a living population. The result is the breed called Heck cattle, "Recreated Aurochs", or "Heck Aurochs", which bears some resemblance to what is known about the appearance of the wild aurochs.

Scientists of the Polish Foundation for Recreating the Aurochs (PFOT) in Poland want to use DNA from bones in museums to recreate the aurochs and return this animal to the forests of Poland. The project has gained the support of the Polish Ministry of the Environment. They plan research on ancient preserved DNA. Other research projects have extracted "ancient" DNA over the past twenty years and their results published in such periodicals as Nature and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. Polish scientists believe that modern genetics and biotechnology make recreating an animal almost identical to aurochs possible. They say this research will lead to examining the causes of the extinction of the aurochs, and help prevent a similar occurrence with domestic cattle.In a similar program, Project Tauros is trying to DNA sequence breeds of modern cattle to find gene sequences which match those found in "ancient DNA" from aurochs samples. The modern cattle would then be selectively bred to try to bring the aurochs-type genes back into a single animal. Johan van Arendonk, a professor of animal-breeding and genetics at Wageningen University is quoted as saying, "It's still a very open question if it all can be done."

The now-extinct aurochs Bos primigenius, which ranged throughout much of Eurasia and Northern Africa during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene, is widely accepted as the wild ancestor of modern cattle. Archaeological evidence shows that domestication of this formidable animal occurred independently in the Near East and the Indian subcontinent between 10,000–8,000 years ago, giving rise to the two major domestic taxa observed today — humpless Bos taurus (taurine) and humped Bos indicus (zebu), respectively. This is confirmed by genetic analyses of matrilineal mitochondrial DNA sequences, which reveal a marked differentiation between modern Bos taurus and Bos indicus haplotypes, demonstrating their derivation from two geographically- and genetically-divergent wild populations.

Domestication of the aurochs began in the southern Caucasus and northern Mesopotamia from about the 6th millennium BC, while genetic evidence suggests that aurochs were independently domesticated in India and possibly in northern Africa. Domesticated cattle and aurochs are so different in size that they have been regarded as separate species; however, large ancient cattle and aurochs "are difficult to classify because morphological traits have overlapping distributions in cattle and aurochs and diagnostic features are identified only in horn and some cranial element

In the 1920s two German zoo directors (in Berlin and Munich), the brothers Heinz and Lutz Heck, began a selective breeding program in the attempt to breed the aurochs back into existence (see breeding back) from the domestic cattle that were their descendants. Their plan was based on the concept that a species is not extinct as long as all its genes are still present in a living population. The result is the breed called Heck cattle, "Recreated Aurochs", or "Heck Aurochs", which bears some resemblance to what is known about the appearance of the wild aurochs.

Scientists of the Polish Foundation for Recreating the Aurochs (PFOT) in Poland want to use DNA from bones in museums to recreate the aurochs and return this animal to the forests of Poland. The project has gained the support of the Polish Ministry of the Environment. They plan research on ancient preserved DNA. Other research projects have extracted "ancient" DNA over the past twenty years and their results published in such periodicals as Nature and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. Polish scientists believe that modern genetics and biotechnology make recreating an animal almost identical to aurochs possible. They say this research will lead to examining the causes of the extinction of the aurochs, and help prevent a similar occurrence with domestic cattle.In a similar program, Project Tauros is trying to DNA sequence breeds of modern cattle to find gene sequences which match those found in "ancient DNA" from aurochs samples. The modern cattle would then be selectively bred to try to bring the aurochs-type genes back into a single animal. Johan van Arendonk, a professor of animal-breeding and genetics at Wageningen University is quoted as saying, "It's still a very open question if it all can be done."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed