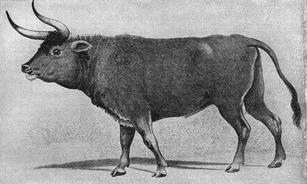

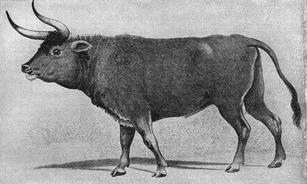

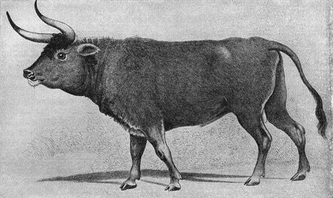

Extincted Aurochs

An Aurochs, from a 19th century copy of a painting owned by a merchant in Augsburg. The original probably dates to the 16th century. The aurochs or urus (Bos primigenius), the ancestor of domestic cattle, was a type of huge wild cattle which inhabited Europe, Asia and North Africa, but is now extinct; it survived in Europe until 1627.

The aurochs was far larger than most modern domestic cattle with a shoulder height of 2 metres (6.6 ft) and weighing 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb). The aurochs was regarded as a challenging quarry animal, contributing to its extinction. The last recorded aurochs, a female, died in 1627 in the Jaktorów Forest, Poland, and her skull is now the property of Livrustkammaren in Stockholm.

Aurochs appear in prehistoric cave paintings, in Julius Caesar's The Gallic War, and as the national symbol of many European countries, states and cities such as Alba-Iulia, Kaunas, Romania, Moldavia, Mecklenburg, and Uri. The Swiss canton Uri was actually named after this animal species.

Domestication of bovines occurred in several parts of the world but at roughly the same time, about 8,000 years ago, possibly all derived from the aurochs. In 1920, the Heck brothers, who were German biologists, attempted to recreate aurochs. The resulting cattle are known as Heck cattle or Reconstructed Aurochs, and number in the thousands in Europe today. However, they are genetically and physiologically distinct from aurochs. The Heck brothers' aurochs also have a pale yellow dorsal stripe, instead of white.

Origin:-

According to the Paleontologisk Museum, University of Oslo, aurochs evolved in India some two million years ago, migrated into the Middle East and further into Asia, and reached Europe about 250,000 years ago. They were once considered a distinct species from modern European cattle (Bos taurus), but more recent taxonomy has rejected this distinction.[citation needed] The South Asian domestic cattle, or zebu, descended from a different group of aurochs at the edge of the Thar Desert; this would explain the zebu's resistance to drought. Domestic yak, gayal and Javan cattle do not descend from aurochs. Modern cattle have become much smaller than their wild forebears. Aurochs were about 1.75 metres (5 ft 9 in) tall, while a very large domesticated cow is about 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) and most domestic cattle are much smaller than this. Aurochs also had several features rarely seen in modern cattle, such as lyre-shaped horns set at a forward angle, a pale stripe down the spine, and sexual dimorphism of coat color. Males were black with a pale eel stripe or finching down the spine, while females and calves were reddish (these colours are still found in a few domesticated cattle breeds, such as Jersey cattle). Aurochs were also known to have very aggressive temperaments and killing one was seen as a great act of courage in ancient cultures

This specimen is from around 7500 BC and is one of two very well preserved aurochs skeletons found in Denmark. The Vig-aurochs can be seen at The National Museum of Denmark. The circles indicate where the animal was wounded by arrows Domestication and extinction:-

The now-extinct aurochs Bos primigenius, which ranged throughout much of Eurasia and Northern Africa during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene, is widely accepted as the wild ancestor of modern cattle. Archaeological evidence shows that domestication of this formidable animal occurred independently in the Near East and the Indian subcontinent between 10,000–8,000 years ago, giving rise to the two major domestic taxa observed today — humpless Bos taurus (taurine) and humped Bos indicus (zebu), respectively. This is confirmed by genetic analyses of matrilineal mitochondrial DNA sequences, which reveal a marked differentiation between modern Bos taurus and Bos indicus haplotypes, demonstrating their derivation from two geographically- and genetically-divergent wild populations.

Domestication of the aurochs began in the southern Caucasus and northern Mesopotamia from about the 6th millennium BC, while genetic evidence suggests that aurochs were independently domesticated in India and possibly in northern Africa. Domesticated cattle and aurochs are so different in size that they have been regarded as separate species; however, large ancient cattle and aurochs "are difficult to classify because morphological traits have overlapping distributions in cattle and aurochs and diagnostic features are identified only in horn and some cranial element

In the 1920s two German zoo directors (in Berlin and Munich), the brothers Heinz and Lutz Heck, began a selective breeding program in the attempt to breed the aurochs back into existence (see breeding back) from the domestic cattle that were their descendants. Their plan was based on the concept that a species is not extinct as long as all its genes are still present in a living population. The result is the breed called Heck cattle, "Recreated Aurochs", or "Heck Aurochs", which bears some resemblance to what is known about the appearance of the wild aurochs.

Scientists of the Polish Foundation for Recreating the Aurochs (PFOT) in Poland want to use DNA from bones in museums to recreate the aurochs and return this animal to the forests of Poland. The project has gained the support of the Polish Ministry of the Environment. They plan research on ancient preserved DNA. Other research projects have extracted "ancient" DNA over the past twenty years and their results published in such periodicals as Nature and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. Polish scientists believe that modern genetics and biotechnology make recreating an animal almost identical to aurochs possible. They say this research will lead to examining the causes of the extinction of the aurochs, and help prevent a similar occurrence with domestic cattle.In a similar program, Project Tauros is trying to DNA sequence breeds of modern cattle to find gene sequences which match those found in "ancient DNA" from aurochs samples. The modern cattle would then be selectively bred to try to bring the aurochs-type genes back into a single animal. Johan van Arendonk, a professor of animal-breeding and genetics at Wageningen University is quoted as saying, "It's still a very open question if it all can be done."

It is commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger (because of its striped back), the Tasmanian wolf, and colloquially the Tassie tiger or simply the tiger.[6] Native to continental Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea, it is thought to have become extinct in the 20th century. It was the last extant member of its genus, Thylacinus, although several related species have been found in the fossil record dating back to the early Miocene.

The thylacine had become extremely rare or extinct on the Australian mainland before European settlement of the continent, but it survived on the island of Tasmania along with several other endemic species, including the Tasmanian devil. Intensive hunting encouraged by bounties is generally blamed for its extinction, but other contributory factors may have been disease, the introduction of dogs, and human encroachment into its habitat. Despite its official classification as extinct, sightings are still reported, though none proven.

Like the tigers and wolves of the Northern Hemisphere, from which it obtained two of its common names, the thylacine was an apex predator. As a marsupial, it was not closely related to these placental mammals, but because of convergent evolution it displayed the same general form and adaptations. Its closest living relative is thought to be either the Tasmanian devil or numbat.

The thylacine was one of only two marsupials to have a pouch in both sexes (the other being the water opossum). The male thylacine had a pouch that acted as a protective sheath, covering the male's external reproductive organs while he ran through thick brush.

Thylacine or the Tasmanian tiger is not exactly like any regal tigers you have seen so far; in fact this tiger is a far cry from the normal tigers! Although now they are considered to be extinct, their existence is still in question due to many reported sightings by explorers. The Thylacine looks less of a tiger and more of a wolf and has few characteristics of a dog as well. This animal was seen in large numbers in the early days but soon their numbers declined due to hunting. The Thylacine sure seems to be one animal that is surrounded by mystery! Here, we shall have an insight into details connected with the Tasmanian tiger.

Description of the Thylacine – Tasmanian Tiger

The Thylacine was a marsupial – these are mammals that are distinguished from other animals due to the presence of a pouch, which is used to carry their young ones. In case of the Thylacine, males as well as females both had a pouch. This was mainly because for the male Tasmanian tiger, the pouch proved to be a form of protection to protect the external organs.

Early depictions of the Tasmanian tiger reveal a strong resemblance to dogs. This Tasmanian tiger looked like a shorthaired dog, which had a big head. It had been referred to as a tiger only because of the presence of stripes on the body. Tasmanian tigers had a yellowish brown colored coat for their body. A rather strange characteristic feature of the Tasmanian tiger was the ability to open its jaw wide to an angle of 120 degrees! It has also been reported this tiger did not really have the ability to run at a high speed. Studies revealed the Tasmanian tiger even hopped at times on the similar lines of a kangaroo!

On an average, the Thylacine was reported to be around 100 – 180 cms in length (from the nose to the tip of the tail) and stood at a height of 60 cms (at the shoulder area). They could weigh up to 30 kgs. The tail of the Tasmanian tiger was stiff and was thicker towards the base. The stripes of the Thylacine were around 15 – 20 in number, which went all across from the shoulder to the base of the tail.

Breeding and Behavior of the Thylacine – Tasmanian Tiger

Breeding period of the Thylacine took place during the winter and spring seasons. Young ones spent their time in the mother’s pouch. When these young ones left the mother’s pouch, they spent time in caves till they reached an age to hunt for themselves.

The Tasmanian tiger was known to be a nocturnal animal by nature. The days were spent in caves and the nights were spent hunting in the forests. The Tasmanian tiger used its strong sense of smell to capture prey in the dark. This animal is also known to be shy in nature. Experts have revealed the Tasmanian tiger preferred to pursue its prey by trotting behind rather than the powerful bursts of speed displayed by tigers.

Habitat of the Thylacine – Tasmanian Tiger

The Tasmanian tiger was native to the Australia and areas of New Guinea. This tiger was known to inhabit wetlands and the grassland areas. It also preferred eucalyptus forests. In areas of Tasmania, the Thylacine preferred to inhabit woodland areas. This was also indicated with the discovery of rock paintings that suggest the Tasmanian tiger lived in that particular area and was also seen approximately 2000 years back!

Mystery surrounding the Thylacine – Tasmanian Tiger

The Tasmanian tiger was reported to be extinct after the 1930s. There were many factors that led to the rapid decline of these animals. The loss of habitat, being hunted by humans and wild dogs led to their extinction. However, a great number of people in Tasmania have reported seeing the Tasmanian tiger in the wild. Although certain unclear photographs were provided, the authenticity of these photographs is still a matter of great debate!

Extincted The Barbary Lion

Extincted The Barbary Lion Lions are generally classified as the Asian lion or the African lion. Both of them have varied physical and social characteristics. But it was the Barbary lion residing in Northern Africa that resembled the Asian lion more than the African lion. Another feature that distinguished the Barbary lion from the rest was that it preferred to dwell in mountainous regions and not in the savanna or open expanses and grassy plains of Africa, or the heavily protected environs of western India. It was separated from the rest of the lion population by deserts on the south, south-east, and east of the Great and Little Atlas. It was also known as the Atlas lion or the Nubian lion. The last Barbary lion in the wild was killed in the Moroccan Atlas Mountains in 1922. Deforestation and encroachment by humans were the other major causes for its extinction from the wild. Two other predators of the Atlas mountain range - the Barbary Leopard and the Atlas Bear are also extinct.

The Barbary lion joined the pantheon of evil predators when they were graphically described in the writings regarding the Roman Empire. Fighting the gladiators and feasting on innocent martyrs. But the extinction of the Barbary lion occurred in stages. It first became extinct in Tripoli in 1700, then in Tunisia due to hunting by Arab and French sportsmen in 1891, in Algeria due to the fact that the Government encouraged tribes to hunt them down in 1899, and finally in Morocco due to the widespread civil war and forest brigands.

The male Barbary lion commonly weighed between 500-600 lbs while the females weighed 300-350 lbs. This is 50% more than what the African lion weighs. Its body was shorter than its Asian and African counterparts but its body could grow up to 11 feet in length. Its legs being shorter contributed to its overall muscular appearance. One distinguishing feature was that its mane extends down the chest through the front legs, through the underside of its belly to the groin. The color of the mane is one of the many variants of blonde depending on the age, sex and physical condition of the lion. Prey included Barbary Stage, gazelle and the Arabic cows. If the opportunity was there then even horses weren’t spared. Carcasses found have indicated that the main method of hunting resembled that of all other lions. It was death by strangulation where the lion would chase down a prey and sink its teeth into the neck. Since it lived in mountain terrain, it had a solitary existence or occasionally lived in pairs. Females raised their young until maturity - approximately 2 years -and then separated from them.

Males and females only came together during the breeding season. Females start coming of age once they are around 2 years old, but do not generally conceive until 3-4 years. Males have the capacity to reproduce at 30 months and but do not tend to produce cubs before the age of 3. Gestation is approximately 110 days, after which 1-6 cubs are born, with 3-4 being most common. The cubs are generally heavily spotted with very dark rosettes and weigh approximately 3.5 pounds at birth.

A DNA analysis of the Asian and African lions would reveal that they are two different sub-species but it is suspected that if such an analysis would be conducted on the Barbary lion we would have a third sub-specie. There are unconfirmed reports that there are a few Barbary lions that exist in captivity in certain North American sanctuaries. Today not more than 15000-20000 lions survive in the wild. If we do not take concrete measures to protest the lion it will not be long that the King of Beasts becomes a folk tale that we narrate to our descendants.

Japanese Sea Lion

Lions are generally classified as the Asian lion or the African lion. Both of them have varied physical and social characteristics. But it was the Barbary lion residing in Northern Africa that resembled the Asian lion more than the African lion. Another feature that distinguished the Barbary lion from the rest was that it preferred to dwell in mountainous regions and not in the savanna or open expanses and grassy plains of Africa, or the heavily protected environs of western India. It was separated from the rest of the lion population by deserts on the south, south-east, and east of the Great and Little Atlas. It was also known as the Atlas lion or the Nubian lion. The last Barbary lion in the wild was killed in the Moroccan Atlas Mountains in 1922. Deforestation and encroachment by humans were the other major causes for its extinction from the wild. Two other predators of the Atlas mountain range - the Barbary Leopard and the Atlas Bear are also extinct.

The Barbary lion joined the pantheon of evil predators when they were graphically described in the writings regarding the Roman Empire. Fighting the gladiators and feasting on innocent martyrs. But the extinction of the Barbary lion occurred in stages. It first became extinct in Tripoli in 1700, then in Tunisia due to hunting by Arab and French sportsmen in 1891, in Algeria due to the fact that the Government encouraged tribes to hunt them down in 1899, and finally in Morocco due to the widespread civil war and forest brigands.

The male Barbary lion commonly weighed between 500-600 lbs while the females weighed 300-350 lbs. This is 50% more than what the African lion weighs. Its body was shorter than its Asian and African counterparts but its body could grow up to 11 feet in length. Its legs being shorter contributed to its overall muscular appearance. One distinguishing feature was that its mane extends down the chest through the front legs, through the underside of its belly to the groin. The color of the mane is one of the many variants of blonde depending on the age, sex and physical condition of the lion. Prey included Barbary Stage, gazelle and the Arabic cows. If the opportunity was there then even horses weren’t spared. Carcasses found have indicated that the main method of hunting resembled that of all other lions. It was death by strangulation where the lion would chase down a prey and sink its teeth into the neck. Since it lived in mountain terrain, it had a solitary existence or occasionally lived in pairs. Females raised their young until maturity - approximately 2 years -and then separated from them.

Males and females only came together during the breeding season. Females start coming of age once they are around 2 years old, but do not generally conceive until 3-4 years. Males have the capacity to reproduce at 30 months and but do not tend to produce cubs before the age of 3. Gestation is approximately 110 days, after which 1-6 cubs are born, with 3-4 being most common. The cubs are generally heavily spotted with very dark rosettes and weigh approximately 3.5 pounds at birth.

A DNA analysis of the Asian and African lions would reveal that they are two different sub-species but it is suspected that if such an analysis would be conducted on the Barbary lion we would have a third sub-specie. There are unconfirmed reports that there are a few Barbary lions that exist in captivity in certain North American sanctuaries. Today not more than 15000-20000 lions survive in the wild. If we do not take concrete measures to protest the lion it will not be long that the King of Beasts becomes a folk tale that we narrate to our d

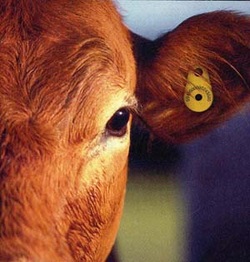

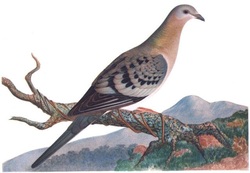

Coextinction: A cause to extinction

Coextinction refers to the loss of a species due to the extinction of another; for example, the extinction of parasitic insects following the loss of their hosts. Coextinction can also occur when a species loses its pollinator, or to predators in a food chain who lose their prey. "Species coextinction is a manifestation of the interconnectedness of organisms in complex ecosystems ... While coextinction may not be the most important cause of species extinctions, it is certainly an insidious one". Coextinction is especially common when a keystone species goes extinct.

Predation, competition, and disease  livestock Before the evolution of hominids, life forms competed with each other and drove one another extinct. Recently in geologic time, Humans have been transporting animals and plants from one part of the world to another for thousands of years, sometimes deliberately (e.g., livestock released by sailors onto islands as a source of food) and sometimes accidentally (e.g., rats escaping from boats). In most cases, such introductions are unsuccessful, but when they do become established as an invasive alien species, the consequences can be catastrophic. Invasive alien species can affect native species directly by eating them, competing with them, and introducing pathogens or parasites that sicken or kill them or, indirectly, by destroying or degrading their habitat. Human populations may themselves act as invasive predators. According to the "overkill hypothesis", the swift extinction of the megafauna in areas such as New Zealand, Australia, Madagascar and Hawaii resulted from the sudden introduction of human beings to environments full of animals that had never seen them before, and were therefore completely unadapted to their predation techniques.

Purebred wild species evolved to a specific ecology can be threatened with extinction through the process of genetic pollution—i.e., uncontrolled hybridization, introgression genetic swamping which leads to homogenization or out-competition from the introduced (or hybrid) species. Endemic populations can face such extinctions when new populations are imported or selectively bred by people, or when habitat modification brings previously isolated species into contact. Extinction is likeliest for rare species coming into contact with more abundant ones; interbreeding can swamp the rarer gene pool and create hybrids, depleting the purebred gene pool (for example, the endangered Wild water buffalo is most threatened with extinction by genetic pollution from the abundant domestic water buffalo). Such extinctions are not always apparent from morphological (non-genetic) observations. Some degree of gene flow is a normal evolutionarily process, nevertheless, hybridization (with or without introgression) threatens rare species' existence.

The gene pool of a species or a population is the variety of genetic information in its living members. A large gene pool (extensive genetic diversity) is associated with robust populations that can survive bouts of intense selection. Meanwhile, low genetic diversity (see inbreeding and population bottlenecks) reduces the range of adaptions possible. Replacing native with alien genes narrows genetic diversity within the original population, thereby increasing the chance of extinction.

Genetics and demographic phenomena  Population genetics and demographic phenomena affect the evolution, and therefore the risk of extinction, of species. Limited geographic range is the most important determinant of genus extinction at background rates but becomes increasingly irrelevant as mass extinction arises.

Natural selection acts to propagate beneficial genetic traits and eliminate weaknesses. It is nevertheless possible for a deleterious mutation to be spread throughout a population through the effect of genetic drift.

A diverse or deep gene pool gives a population a higher chance of surviving an adverse change in conditions. Effects that cause or reward a loss in genetic diversity can increase the chances of extinction of a species. Population bottlenecks can dramatically reduce genetic diversity by severely limiting the number of reproducing individuals and make inbreeding more frequent. The founder effect can cause rapid, individual-based speciation and is the most dramatic example of a population bottleneck.

Causes for Extinction

As long as species have been evolving, species have been going extinct. It is estimated that over 99% of all species that ever lived have gone extinct. The average life-span of most species is 10 million years, although this varies widely between taxa. There are a variety of causes that can contribute directly or indirectly to the extinction of a species or group of species. "Just as each species is unique," write Beverly and Stephen Stearns, "so is each extinction ... the causes for each are varied—some subtle and complex, others obvious and simple". Most simply, any species that is unable to survive or reproduce in its environment, and unable to move to a new environment where it can do so, dies out and becomes extinct. Extinction of a species may come suddenly when an otherwise healthy species is wiped out completely, as when toxic pollution renders its entire habitat unliveable; or may occur gradually over thousands or millions of years, such as when a species gradually loses out in competition for food to better adapted competitors. Extinction may take place a long time after the events that set it in motion, a phenomenon known as extinction debt.

Assessing the relative importance of genetic factors compared to environmental ones as the causes of extinction has been compared to the nature-nurture debate. The question of whether more extinctions in the fossil record have been caused by evolution or by catastrophe is a subject of discussion; Mark Newman, the author of Modeling Extinction argues for a mathematical model that falls between the two positions. By contrast, conservation biology uses the extinction vortex model to classify extinctions by cause. When concerns about human extinction have been raised, for example in Sir Martin Rees' 2003 book Our Final Hour, those concerns lie with the effects of climate change or technological disaster.

Currently, environmental groups and some governments are concerned with the extinction of species caused by humanity, and are attempting to combat further extinctions through a variety of conservation programs. Humans can cause extinction of a species through overharvesting, pollution, habitat destruction, introduction of new predators and food competitors, overhunting, and other influences. Explosive, unsustainable human population growth is an essential cause of the extinction crisis. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 784 extinctions have been recorded since the year 1500 (to the year 2004), the arbitrary date selected to define "modern" extinctions, with many more likely to have gone unnoticed (several species have also been listed as extinct since the 2004 date).

Pseudoextinction  Descendants may or may not exist for extinct species. Daughter species that evolve from a parent species carry on most of the parent species' genetic information, and even though the parent species may become extinct, the daughter species lives on. In other cases, species have produced no new variants, or none that are able to survive the parent species' extinction. Extinction of a parent species where daughter species or subspecies are still alive is also called pseudoextinction.

Pseudoextinction is difficult to demonstrate unless one has a strong chain of evidence linking a living species to members of a pre-existing species. For example, it is sometimes claimed that the extinct Hyracotherium, which was an early horse that shares a common ancestor with the modern horse, is pseudoextinct, rather than extinct, because there are several extant species of Equus, including zebra and donkeys. However, as fossil species typically leave no genetic material behind, it is not possible to say whether Hyracotherium actually evolved into more modern horse species or simply evolved from a common ancestor with modern horses. Pseudoextinction is much easier to demonstrate for larger taxonomic groups.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed